Series links: Prologue Part A Part B Part C Epilogue

US historical background (1946 to 1954); the “Delinquency Problem”

This is a series of three posts on the American Comic Book Codes and their development. See the bottom of this article for general references used for this post, as well as subsequent posts. Specific references are also linked throughout the body of this post for your attention. Additional references will be included in the posts that follow this one.

This blog post will be posted this Wednesday on Substack as part of my comics history and analysis posts. Please check out Henry Brown’s excellent article for Liberty Magazine on Wertham and the furor around Pre-Code Comics here on Substack.

At the conclusion of World War II, the United States was left as the Last Man Standing of the world’s major industrial powers. It would take almost a decade before the some of the other major combatants would be recovered enough to offer significant competition to the industrial powerhouse of the United States of America.

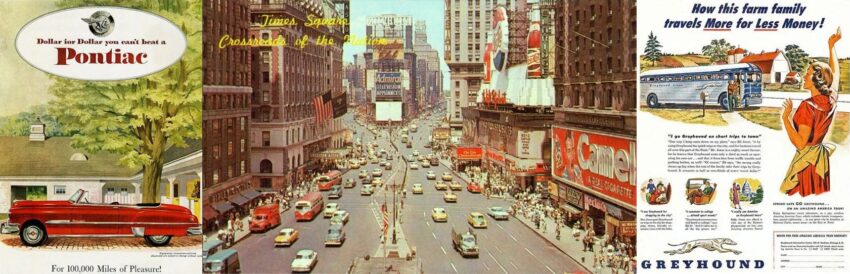

After the signing of the Japanese surrender, the US turned the utilization of its industrial capacity from conflict to commerce. The engines of war became the American engines of production for labor saving devices, fashion, travel, and entertainment, heralding a bountiful and prosperous future for all.

That’s how the story goes, at least.

Housing and Employment

Housing after the war was tight. The long Depression followed by the World War led to housing construction not keeping pace with demand of people moving to larger cities from more rural areas, the repatriation of US military members from overseas locations, plus the post-war Baby Boom of new children. Over 15 million troops were in need of repatriation after the victory over Japan, though establishment of occupation forces in both Japan and Europe would keep US troops on regular rotations in these regions.

- Both the Depression and World War II had moved significant numbers of people away from rural areas to more urban ones from about 1900 to 1945.

- Suburbia became a popular solution to housing issues — planned communities of single-family dwellings outside the more vertical urban centers where new construction was difficult or impossible

- Housing developments such as Levittown, Pennsylvania sprang up to accommodate a large part of that demand

- Modern conveniences — washer and dryer, modern kitchen ranges, wall-to-wall carpeting, and more — were often used as a lures to attract people to suburban developments.

- Similar innovations meant that fewer people had to farm the food needed by the nation. Motorized farm equipment replacement of animal power accelerated. Rural flight continued due to the apparent demand for farmers diminishing.

- Companies closed or converted some of their wartime facilities, while others expanded into fields that leveraged war-time work. Latent demand for other fields, such as construction, helped bring new businesses online in this period.

- This general growth in the economy moved or expanded some business operations to more remote locations, which typically meant that housing would be suburban development to provide for workers who took the jobs.

- The job market vacillated between lack of adequate employment for newly returned service members and companies hunting skilled workers for almost ten years after World War II ended. Service members graduating from trade or academic programs under the “GI Bill” programs gradually helped stabilize this fluctuating job market.

Travel

- Cars became the dominant transportation mode in suburban areas; train stations with drop-off or parking for suburban commuters shuttled workers into urban areas where parking was at a premium; urban areas continued to rely on busses, taxis, and short-distance light-rail lines for transport

- Transit to train stations meant a build up of highways; commuter traffic into areas near employment site in or near larger metropolitan areas or new suburban developments slowly became the norm

Entertainment

Most entertainments outside of small social functions, religious services and events, reading, and perhaps radio pre-WW II was often found in more urban settings — movies houses, theaters for plays, concert halls, nightclubs — located inside larger cities and within towns near larger cities, being dependent upon regular revenue streams. These venues could be expensive to extend or move those locations to suburban ones as populations shifted there, and many were controlled by larger corporations, such as theater chains being owned by movie studios.

- Drive-in theaters, road house restaurants and clubs, golf and swim clubs opened in suburbia as demand and limited competition made them profitable

- Movie theaters suffered after the War due to reduced attendance and displacement of people from urban to suburban locations

- Studios were found by the federal government to be behaving in a monopolistic manner. In 1948, studios were forced to divest themselves of the movie theater chains that they owned. This made it more difficult for theaters to invest in expansions in suburban areas

- The Studio System itself was essentially dismantled during the late-1940s and early- to mid-1950s due to a series of legal maneuverings, financial wrangling, and media embarrassments. See this article and this article for some short summaries of its rise, fall, and demise. Keep the term “block booking” in mind for future discussions of comic book issues.

- From 1925 through about 1950, printed newspapers, magazines, and books had good uptake by the general public in this period, then began to gradually fall off in the late 20th Century.

- With the advent of television, movie going and other outside-the-home entertainment habits began to change as well. The “one-eyed monster” was now affordable for most Middle-American Families and became one of the dominant entertainment forces in the late-1950s. It’s immediate popularity was clear: always available in your own home with all its comforts, no additional expenditures in money or time to access it, and no need to travel to see it.

Communications and entertainment vigorously competed for the predominant place in the American home in the post-war period. By 1955, about 65% of homes had at least one television as well as landline telephone service. By 1960, television outpaced landline telephone adoption. Radio was gradually sharing its predominant media position with television, both at over 90% uptake in the mid- to late-60s.

Source link for the above image.

Politics and Military Conflicts

Allies in World War II became enemies almost overnight as European lines were drawn between countries inside and those outside of the Soviet Union. This was the period in which the Cold War was initiated between Western powers and the growing Communist blocs centered about the Soviet Union and the newly-formed People’s Republic of China. A “cold war” primarily due to the existence of the recently developed nuclear weapons used by the United States against the Japanese to bring an end to World War II. While the Berlin Wall would not appear until the 1960s, the Berlin Airlift was a clear and immediate sign of this separation, reported heavily by the Media, along with threats to independent countries of falling under Communist spheres of influence.

Organized Crime and Juvenile Delinquency

Organized Crime became a topic of concern, but was really a low-burn hold-over for the Public since the Prohibition Era, where criminal organizations had filled demand gaps created by the Twentieth Amendment to the US Constitution. Believing that morality could be legislated, the US experimented with the relatively total legal ban on the production and consumption of alcohol, rather than attempting the more arduous task of moral education regarding alcohol’s proper use and its abuses.

The Great Depression saw some of these criminal elements lionized as well as vilified for their actions. World War II meant that if the Public had a desire to solve this problem, it would take second, third, or even lower place than the immediate concerns of armed national conflict.

This will also be a point for later discussions.

The larger issue of organized crime that was a holdover from the Prohibition and Depression eras was of concern and was addressed by Federal, State, and municipal governments now that WWII concerns were diminished. The Public was wondering how deep the involvement of Organized Crime went in their daily lives and why juvenile delinquency was still on the rise.

Delinquency rates among youth, especially in larger urban areas, had increased significantly over the period of WW II as well as over the post-war period. Some urban areas were experiencing increases in delinquency of up to 33% in the immediate post war period. Both male and female delinquency was on the rise from 1942 onward according to FBI and police statistics.

The Public wished to know what could be done to discover the depth of the effects of crime and delinquency and to reverse these criminal trends. The Media, both news and entertainment, attended closely to both these issues. Public discussion prompted both municipal and State investigations of organized crime and juvenile delinquency. Congressional committees took up both questions in the late 40s and early 50s, and the rising star of Media, television, would play a key role in both Federal investigations.

RESULT OF THE ABOVE: The US Public’s stress level was *HIGH* from the 40s through the 60s

Despite the glowing hagiography attributed to the 1950s, it also had its own brand of looming specters that haunted the Suburban paradises, just as we have our societal and political burdens to bear in the 21st Century along with some positive things, much as Dickens had pointed out us.

During World War II, some of the factors involved in the delinquency rise included absence of one parent due to war service or post-war occupation service. There was the possibility that the other parent might also be involved in support activities for the conflict and to earn money due to absent or missing spouse, leading to less supervision of children at home during the war.

Setting aside organized crime questions, there were many potential factors that likely influenced growth of juvenile delinquency in the post-war period. The social disruptions involving housing, moving to areas in need of employees, encountering differing social norms between urban and rural with these moves, the increased stress on services and resources due to the increase in children born after the war (the Baby Boom), and overcrowding in some areas and lack of manpower in others plagued the US well into the 1950s.

The rise of Suburbia led to new social norms, with additional leisure time due to more affordable mechanical conveniences, but increasing stress due to the new nature of travel between urban and suburban areas.

Note that here, as with several other stressors that families faced, many of these factors could not easily be addressed or were beyond parents’ influence. Once the issues of education, job, and housing were resolved for the post-war family, there was still the new reality of living in a still-changing United States. The daily commute which took fathers out of the home due to urban jobs was typically unchangeable, unless a new job could be found and the family moved — which was also disruptive.

Suburban vs Urban life was still being negotiated. Miltown (followed later by Valium), Thorazine, and Thalidomide originated in this period of American life, heralding the wider use of pharmaceuticals by Americans, as well increasing prescriptions for antidepressants and “mood stabilizing” drugs outside of clinical patients and institutionalized individuals.

The international situation with the growth and influence of the Soviet Union and Communist China was not within the control of the average US citizen. Nuclear weapons development and testing by three of the nuclear powers was ongoing above ground, under sea, and below ground. This included the development and tests of the hydrogen bomb, which removed the upper limits of destructive power on nuclear weapons. These were an existential threat that the Media kept in full view of the Public through newspapers, radio, movies, and the rapidly growing medium of television.

The Korean War/Conflict opened only five years after World War II ended, lasting three years from 1950 to 1953, further disrupting families and communities. Many countries went under the Communist umbrella in the late 40s and 50s, giving evidence to the American public that Communist aggression was a clear and present threat to the Western democracies.

The specter of organized crime appeared to be out of the span of control for the average American, as did aspects of juvenile delinquency.

The demand on government to take a hand to solve some of these issues was growing via civic groups, religious organizations, and parents organizations.

But, where parents could become involved if there was a threat to their children that might be curtailed or eliminated, why wouldn’t they take action? Why wouldn’t they be determined to remove that threat?

Entertainment products were within that parental span of control, as many children in the 5- to 18-year old range were dependent upon their parents for support, such as monetary allowances and motorized transportation. The two-car family predominance in the United States began closer to the 1970s.

Movies, music, theater, television programs — and comic books. Here parents could take a direct hand in controlling whether or not their children would be exposed to potentially detrimental influences.

Minors were the responsibility of their adult parents until they reached the age of majority. Why should anyone be shocked if parents chose to limit their children’s access to some potentially detrimental influence?

Comic books were in the cross-hairs of concerned parents, and had been since at least the early 1940s. Parents, teachers, librarians, religious leaders, and some medical professionals began to organize to make their concerns known and to take action if needed.

Some details in the next post on how the supposed powder keg of the American Comic Book Code was primed and how its fuse was lit.

REFERENCE MATERIALS USED FOR PART A

References used here include, but are not limited to the following books and testimonial references. I strongly recommend to you all four books for your reading pleasure, and specific links that host source material from the events. These are essential if you want to understand these events.

Layers of myth have built up and surround the comic book “censorship” that followed U.S. Senate sub-committee hearings in 1954. Without reading source materials or materials that capture the most direct evidence and testimony from the principle participants and witnesses of these events, you will likely find yourself in the loop of blaming a single party due to misinformation that has circulated for decades around these events.

Book ISBNs are provided for commercial copies of these books which are available through various book sellers and outlets.

I. Books.

Seduction of the Innocent, Frederic Wertham, 1954 [ISBN-10: 159683000X; ISBN-13: 9781596830004] – The book that everyone points at, but likely few have actually read, other than for a pull-quote. Read it if you have any hope of understanding what Wertham was about, what he wanted, and how he came to the conclusions he came to over more than seven years of researching comic books, specifically crime and horror books. You likely won’t agree with all of his opinions or his conclusions, but you may be surprised by what he intended, and what he wanted to accomplish.

Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, Amy Kiste Nyberg, 1998 [ISBN-10: 087805975X; ISBN-13: 978-0878059751] – Nyberg provides a well-researched yet accessible analysis of the events associated with the Public’s concern over comic books, the juvenile delinquency problem, the Senate hearings, as well as associated events that contributed to the unfolding of events; read this book if you read nothing other than Wertham’s book.

Forbidden Adventures: The History of the American Comics Group, Michael Vance, 1996 [ISBN-10: 0313296782; ISBN-13: 9780313296789] – Vance provides a history of the American Comics Group (ACG) and its long-time editor, Richard Hughes, as well as testimonies from assistant editor, AGC freelance writer, and future academic, Norman Fruman (do some research on him as well). Chapters 11 and 12 are especially relevant to this discussion.

The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, David Hajdu, 2009 [ISBN-10: 0312428235; ISBN-13: 978-0312428235] – Hajdu provides a wealth of testimonial material from publishers, writers, and artists, as well as those people associated with comic book distributors, the CCMA, and the CCA.

II. Articles and Transcripts.

Juvenile delinquency (comic books): Hearings before the Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Eighty-third Congress, second session, pursuant to S. 190. Investigation of juvenile delinquency in the United States. April 21, 22, and June 4, 1954 – [LINK] – These are written transcripts from the Senate Subcommittee hearings held in New York City. Portions of the hearings were televised, to include testimony by Wertham and other witnesses.

Dig in, kids. Again, you likely won’t understand this issue until you get into the actual material from the hearings and the discussions had by the principles involved in the Comics Code creation and adoption.