Series links: Prologue Part A Part B Part C Epilogue

Parents being “concerned” and “angry” doesn’t equate to them being “afraid”

Note 1: this post will also appear on Substack shortly, for various levels of shortly.

Note 2: I am purposefully not including direct references to quotes, paraphrases, or summaries from the four books that I use as my primary references. The texts are neither long nor difficult to read, and if you are at all interested in this topic, then my opinion is you should read all of those books to help you understand, and not rely on my pull quotes for understanding. This is neither a reference work nor an academic one. It’s sort of a group of book reviews on steroids.

A very abbreviated list of selected highlights of the Golden Age of Comic Books (1933-1956) follows below. You can skip this for now if you choose, but we will refer back to some of these details later.

- 1933 – The first modern comic book is published: Famous Funnies; most comic books are reprints of newspaper strips, eventually adding short comics from in-house or freelance creators.

- 1935 – National Allied Publications publishes Detective Comics #1, an anthology series of adventure tales, mysteries, detective/police procedurals, and crime-related stories; Batman was introduced in Issue 27 in 1939.

- 1938 – The first costumed hero of the Golden Age, Lee Falk’s The Phantom, appears on newsstands, followed a few months later by the first costumed superhero, Superman. Comics are still primarily anthologies, typically featuring a lead story featuring the title character with backup stories that may or may not be related to the title character; Dell Publishing formed a partnership with Western Publishing under the Dell, Gold Key, and Whitman comic imprints to build a comic book publishing and distribution system that at its peak would hold over 40% of the comic book market.

- 1939 – Timely Comics (Marvel) introduces the Human Torch and Prince Namor the Sub-Mariner; Sandman introduced by National Comics (DC).

- 1940 – Captain Marvel appears and rapidly overtakes Superman in popularity at the newsstands; many superheroes similar to Captain Marvel and Superman appear from several comic publishers over the next five to seven years; Will Eisner’s The Spirit is debuted as a Sunday newspaper supplement; Flash, Hawkman, Green Lantern, Atom, Spectre, Dr Fate, and Hourman are created; Gardner Fox creates the Justice Society of America, which is the first cross-over of superheroes between two comic companies — All-American Publications & National Comics Publications (which had a partner company, Detective Comics). All three would merge into National Periodical Publications in 1946, then rename to DC Comics in 1977.

- 1941 – Captain America, Wonder Woman, Blackhawk, and Dr. Mid-Nite are introduced; patriotic heroes and superheroes spring up and begin to dominate the comics during the war years.

- 1942 – the first ongoing Crime genre comic, Crime Does Not Pay, is published by Lev Gleason; Gleason will be a dominant force in the comic book field through 1955, primarily with four core titles, two of which were Crime comics.

- 1946 – Superheroes begin to rapidly decline in popularity after World War II; action & adventure titles, to include jungle/African/Asian/South American settings, crime, detective, science fiction, and mystery are still popular.

- 1947 – Joe Simon and Jack Kirby (creators of Captain America) introduce a new comic book genre: the Romance Comic — Young Romance debuts and the genre flourishes over the next 10 years, lasting well into the 1970s at both Marvel and DC; William “Bill” Gaines takes over his recently deceased father’s (Max Gaines, former All-American Comics owner) comic book company, EC Comics.

- 1948 – the first ongoing Horror comic book, Adventures into the Unknown, is published by the American Comics Group (ACG), featuring stories by Frank Belknap Long who, with August Derleth, expanded and advanced the H.P. Lovecraft ‘universe’ of horror stories.

- 1949 – Most superhero stand-alone titles have been canceled or shifted to other genres to meet changing customer demand; Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman are the few superheroes at National with their own titles; at Atlas Comics (Marvel), Captain America, the Human Torch, and Sub-Mariner will not have their books for long, though a very brief revival was attempted in the mid 50s; Crime and Romance are two of the popular genres.

- 1950 – Bill Gaines brings out his new line of comics in the Horror, Crime, and Science Fiction genres; these books attract an older audience of readers, but are still marketed via newsstand with other comic books read by younger children. Companies, such as Lev Gleason, make statements that their comics are for “adult readers”.

- 1952 – Comic book readership and sales hit a peak with just over 500 titles on the market; Crime and Horror are estimated to be about 15% to 20% of the comics produced, while Romance accounts for about 10% to 15% of production; estimates show about 100 to 120 million comics are produced per month.

- 1954 – Comic readership and circulation were on a decline, with just over 400 titles on the stands; about 90 million issues of comics found their way to the stands every month. Crime, Horror, and Romance were still very popular genres.

- September/October 1954 – The Comic Code Authority comes into existence and begins its work.

- 1956 – The Flash is reimagined and reintroduced by National Periodicals in Showcase Issue 4. This is recognized as the beginning of the Silver Age of Comics.

From a 1943 survey commissioned to find out who was reading comic books, it was found that 95% of 8 to 11 year-old children read comics, 84% of 12 to 17 year-old children were comic readers, and about 35% of people in the 18 to 30 year-old range also read comics. Generally, in the 1935 to 1955 period, the bulk of comic book readership was in the 8 to 15 year-old range.

That meant incredible market penetration for one type of printed media. Circulation numbers are only estimates, but consider that in the early- to mid-1940s, about 25 million comics per month were estimated to be in circulation. That figure rose to a peak of about 120 million comic per month in 1952 (from the Congressional Record), falling to about 90 million per month in 1954 (as reported in the Senate hearings), to about 26 million per month in 1959/1960. Online tools can be helpful nailing down these numbers, but until 1960’s change in US Postal requirements, they are sometimes a wag.

Prices of all of these books were 10 cents, the prices of comics rising to 12 cents in 1961. 25 million copies per month, or 300 million copies per year, meant that gross revenues due to sales could be as high as $30 million per year, though it is usually safe to assume that only 50% of comics sold to consumers and the remainders were returned to publishers through the wholesale and distributor chains. In 1952, that would amount to about 1.4 billion comics annually for a potential revenue of $140 million, or a likely realized average revenue floor of $70 million per year.

Put that value in your favorite inflation calculator, and we see that in 2024 dollars, the comic book industry likely realized gross annual revenues upwards of $832 million per year. Mid-1940s average revenues were about $175 million per year in 2024 dollars. Revenues were falling from 1952 forward, and by the time the hearings rolled into NYC in 1954, that lower bound figure had dropped to $642 million per year in 2024 dollars.

As the Senate Subcommittee Chair, Sen Hendrickson stated on the Senate floor prior to the NYC comic book hearings, “The comic-book industry is big business, Mr. President.” It’s important to remember that item: comic book publishing was a major business concern in 1954. Those dimes added up!

Since the majority of comics readers were somewhere between 8 and 15 years of age, there was thought that children were being exploited or threatened by Crime and Horror comic book exposure by a select few business concerns for the sake of their profit. The ads found in comics were also concerning to parents if these were magazines for children in the 8 to 15 year-old ages.

During the war years, parents, civic groups, and religious organizations became concerned over the increase in juvenile delinquency and associated criminal events. That comic books of the period might be a potential problem was brought forward by teachers, librarians, and church leaders to be investigated and addressed if needed.

Some comic books contained frequent violent action, graphic depictions of injury, sometimes sexual innuendo and sexual situations (such as trussing up females and placing them in threatening situations), scanty dress of female characters, and the common practice of putting these things on the cover of the comic book, sometimes showing scenes that never appeared in the book itself. Some groups were concerned that comics might have a negative effect on some children and wanted to determine if this was so. Crime comics became an obvious area of focus for these groups.

“Crime” needs some explanation. The Crime genre of the Golden Age was not the same as the “Police/Detective” genre, and it boiled down to a matter of “focus” or “point of view” (POV).

In the Police/Detective genre, the primary focus, or POV, is on the law enforcement group or the private detective. The typical narrative follows the protagonists as they investigate and solve crimes. This often involved chases, shoot-outs, interviews, investigative work, and other shenanigans, primarily from the point of view of the good guy trying to catch the bad guy. There might be cuts to the antagonist’s POV in the story, but these are limited compared to the protagonist POV.

The Crime genre, on the other hand, primarily followed the criminals’ POV and focused the main thrust of the story on his actions. This was often a story that gave a brief rundown of the criminal’s life and how he turned to crime, and not infrequently drew on actual criminals’ histories, as well as abbreviated synopses of criminal acts they committed over a period of their lives. The story would wind down very quickly to show or even just state that the criminals were captured and punished severely for their crimes. Law enforcement activities were most often limited to shoot-outs or the final arrest before the story’s conclusion.

Focus is important when writing to a genre. A POV of unrepentant Evil is might be bad for you (both author and reader) in the long term versus taking a POV that instead focuses on the Good. We will see that this is a hinge point in the Pre-Code comic book contention. See this post by K. M. Carroll for more discussion on this Good vs Evil focus.

Concerns were raised that the primary focus on the criminal and criminal events rather than on the people working to stop the criminal’s actions might give impressionable children the wrong message when it came to crime and socially-beneficial morality. Would the criminal acts look enticing to more impressionable readers? Would these materials be something that should not be in the hands of children below a certain age?

This was the concern of various parents organizations, parent-teacher groups, librarians, and church groups. Municipalities and medical professionals became involved, and this is where Dr Fredric Wertham enters the picture.

Wertham was a practicing clinical psychiatrist licensed in New York State, with patients at various locations and facilities within and around New York City. He was an early proponent of mental hygiene and the potential effects of environment on the developing minds of children. Wertham had noted that many of his juvenile patients who showed signs of deviant and delinquent behavior were also intent readers of comic books, typically ones more violent in nature. He noted that these patients typically bought many more comic books than other children, read them repeatedly and sometimes horded them, more rarely traded and sold them among friends, and he suspected that some committed crimes to obtain them.

Wertham and several colleagues who worked at the same hospitals as well as a free/low-cost psychiatric clinic in downtown NYC began to notice and record these observations in clinical records of patients. Additionally, they began to assemble collections of comic books that represented some of the stories and artwork that they believed had either the potential for longer-term harm due to exposure or the material was generally not beneficial to proper socialization and moral development in children.

Wertham began speaking to interested parents groups and other civic organizations in the mid-1940s about these findings obtained within these clinical observations and reviews of case files. He became a proponent for preventing or minimizing access of violent and anti-social comics by children until they had developed a more complete moral and social foundation. While his personal choice would have been to ban these magazines so children could not access them, his stated desire to the Senate Subcommittee and within his book was to ensure that such comics could not be sold to children under the age of 15 or 16.

By the time 1954 rolled around, Wertham was further concerned that the publishers, distributors, and wholesalers could not be trusted to abide by any restrictions other than legally imposed ones, implying that their sole motivation was monetary in nature.

Legal action against comics increased from 1943 to 1948, specifically crime-related ones and those claimed to be salacious in nature, with many municipalities and States taking action to limit or ban the distribution and sale of Crime-related publications of various types. This activity saw a peak in the 1940s with States such as New York and California enacting sweeping bans on Crime publications. The book and magazine publishers fought these bans, and in 1948, the publishers won a significant legal battle at the Supreme Court.

The 1948 US Supreme Court decision in Winters v. New York struck down dozens of State laws and municipal bans on the distribution and sale of Crime books and magazines. These restrictions were found to be a violation of the 1st and 14th Amendments to the US Constitution, creating a prior restraint situation under how the various laws and codes were written. The ruling affirmed that freedom of expression and speech covered not only creating the magazine or book, but also extended to the distribution and sale of the material as well.

With this ruling, Crime comics began to increase in both the number of titles that existed and the number of issues printed in a title’s monthly run.

The concerns voiced by parents and interest groups did not escape the attention of some comics publishers and distributors, even in the early war years. Larger publishers, such as Fawcett, Dell, Lev Gleason, and National Periodicals, established internal review boards for materials slated for publication — or at least selected samples of them — and offered assurances that the books met internally promulgated standards of practice that would ensure books produced under these would be safe for younger readers. Some smaller companies and Timely (Marvel) had paid consultants and informal boards who served similar functions. Questions arose about other publishers who did not advertise such boards or consultants and what their standards might be. Two examples of comics review board notices to parents are shown below.

Because of the concerns raised by the Public and governmental bodies, in 1947 a group of publishers and distributors formed a trade association named the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers, or ACMP, and rolled it out for public view in 1948.

Founding members of the trade association included Phil Keenan (Hillman Periodicals), Leverett Gleason (Lev Gleason Publications), Bill Gaines (EC Comics), Harold Moore (Famous Funnies publisher), Rae Herman (Orbit Publications), Frank Armer (distributor), and Irving Manheimer (distributor). George T. Delacorte, Jr., founder of Dell Publishing served as president, and Manhattan attorney, Henry E. Schultz, served as the executive director for the organization.

The ACMP developed a Comics Code for its members which was based on the Motion Picture Production Code, often referred to as the “Hays Code”.

If you are unfamiliar with the MPPC and why it was instituted, please take a few minutes to review the following informative links.

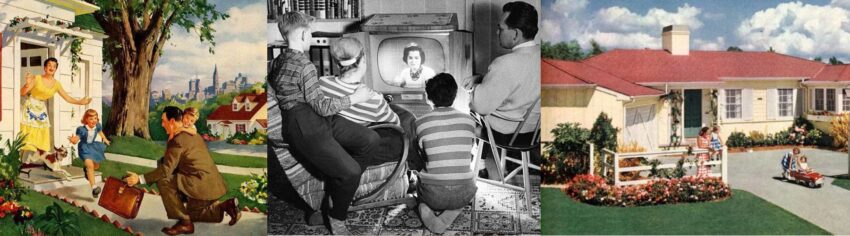

TL;DR: What you see with movies in the 20s and 30s is a similar situation that the Public faced with comic books in the 40s and 50s. The Public didn’t like what was going on in Hollywood and on their movie screens. The MPPC was put in place because the movie studios and movie theaters feared bad press, boycotts of their films, and loss of revenue.

Here is the ACMP Code for you to review.

The ACMP Publishers Code reads:

- Sexy, wanton comics should not be published. No drawing should show a female indecently or unduly exposed, and in no event more nude than in a bathing suit commonly worn in the United States of America.

- Crime should not be presented in such a way as to throw sympathy against the law and justice or to inspire others with the desire for imitation. No comics shall show the details and methods of a crime committed by a youth. Policemen, judges, Government officials, and respected institutions should not be portrayed as stupid, ineffective, or represented in such a way to weaken respect for established authority.

- No scenes of sadistic torture should be shown.

- Vulgar and obscene language should never be used. Slang should be kept to a minimum and used only when essential to the story.

- Divorce should not be treated humorously or represented as glamorous or alluring.

- Ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible.

The problem with this code was that it was essentially enforced internally by each publisher, though the Executive Director and his staff members would provide such reviews for individual comics if requested. Funding for reviews and public affairs communications was provided by association members, on the order of $2,000 annually for each member organization. Additionally, not all publishers and distributors joined the association, so it did not apply industry-wide.

Despite calls for additional laws and government intervention, the history of Prohibition and the 1948 SCOTUS Winters decision indicated that few legal restraints at Federal, State, or municipal levels would withstand judicial review. In addition, any such restrictions would require money and manpower for enforcement.

The preferred Federal Government method in such cases was that the organizations or trade groups established standards, which they would enforce among members, then government bodies could review how well the organization complied with their own internal processes and standards.

But, the ACMP was already failing relative to its own Code by the time Senate hearings were to take place in 1954. What to do? This was exactly as Dr Wertham had claimed. What could be done other than passing restrictive laws that were then strictly enforced?

But, why did the Senate have hearings about Comic Books in the first place?

The 1951 Senate hearings on organized crime had already reviewed some aspects of comic books, and it had also made a determination that comics were not linked to juvenile delinquency, at least as far as evidence presented to the committee at that time had demonstrated.

Though delinquency statistics were down slightly from previous years, the 1953 Public was not satisfied. In an interesting point raised by Hadju in his book, concern was heightened about delinquency by the repatriation of American prisoners of war after the Korean War cease-fire was signed. Some POW’s behavior upon return from captivity raised speculation about brainwashing and indoctrination by their captors. Repatriated POWs showed some signs of mental conditioning and passivity, as though while in captivity by the Communist Chinese and North Korean forces their mental processes and behaviors had been changed somehow. Again, existential concerns moved parents and civic groups to ask for a reason why juvenile delinquency existed and what could be done to reverse it.

One of the items the general public asked the Senate to address was the question of Crime and Horror comics. Ergo, the Subcommitte took up comic books again, even though the previous organized crime investigation had found no solid connections between comic books and delinquency.

The public asked for some type of action be taken to address this concern affecting their children. At the same time, Dr Wertham was completing his book, The Seduction of the Innocent.

In his book, Dr. Wertham cited the historically slow pace of adoption of child labor laws and the public health issue of mandating clean drinking water. He pointed out how in both cases, monied interests won out over legal restraints for years, often decades, before both issues were recognized either as proper moral and ethical stances or good societal and economic ones.

While he did not hold any love for comic books in either his Senate testimony or in his book, Wertham did not demand that comics be banned for any other issue than to be protective of children in their developmental years. He was indifferent to comic book reading by adults.

In his book, Wertham in fact stated that pornographic cartoons, often referred to as “Tijuana bibles” had a more proper moral standing than Crime and Horror comics. He asserted that at least in the pornographic comics there were typically two willing parties engaged in a consensual sexual activity, where in Crime and Horror comics, women were more often the victims of abduction and bondage, threatened with violence and rape, as well as assaulted, battered, and murdered.

Wertham’s request to the Senate essentially boiled down to establishing a law that no Crime, Horror, or similar genre comics could be sold to any child under the age of 15 or 16.

Quelle horreur! The man was a monster!

In his book, even Wertham thought television could be an educational boon, if it could only grow out of its “comic book phase.” Interesting how most media is assumed to be a “Boon to Mankind” in its early adoption phase and will grow to be a positive. Somehow.

Television was a net negative for organized crime figures in 1951, such as Frank Costello during his Senate hearing testimony, and a net positive for both the Senate Committee and Senator Estes Kefauver, who demonstrated that he was quite adept at using the Media for effect within the televised organized crime hearings.

Television and mass media would also turn out to be a net negative for comic book publishers, distributors, and wholesalers in 1954. But not as big a negative as the comic book business itself.

The Run-up to the Hearings

The actions of the comic companies producing Crime and Horror began radically pushing the envelope from 1952 until the 1954 hearings. Companies began to show more graphic depictions of violence, horror, bodily mutilation and decay, and images intended to shock the reader. The appeal to prurient interest in terms of sexual innuendo, brutal crimes and revenge, and mocking of various social and cultural norms became egregious with many publishers.

At the same time, comic book publishers and editors pushed back on comic book critics, too often in a very insulting and tone-deaf manner. It was a clear clash of New York City vs The Rest of the Country sensibilities at play. Two articles discussing the late 40s and early 50s back-and-forth, are included here and here.

One of the most telling chapters in David Hadju’s book, Ten-Cent Plague, deals with the in-fighting and squabbles over the release of EC Comics title “Panic” and highlights the lack of cultural awareness Bill Gaines, Al Feldman, and Harvey Kurtzman possessed relative to the audiences outside of their personal bubble in New York City.

The issue of “Panic” not only created permanent rifts within the EC editorial offices between Feldman and Kurtzman during their time at the company, but it also demonstrated to opponents of the Crime and Horror comic books that no boundaries would be obeyed by publishers, that no insult to culture or religion was beyond them, and that the publishers would continue to claim that they were doing nothing wrong in marketing to children under the 15 years of age while demanding that no restrictions be placed upon them.

I strongly urge you to read Chapter 11 of Hadju to understand the bonfire that was being built by EC and other comic publishers, and how EC willfully dumped kerosene on it before gleefully lighting a match.

The end result of the accelerating cultural and social boundary violations by comic book publishers gave ample fodder to the critics of comics. Many who did not agree with Wertham’s methods and arguments now came around to some of his conclusions regarding exposing children to the environment Crime and Horror comics created. Some critics even joined Wertham in advocating for banning certain genres of comics. Parents outside of New York City who were already intolerant of what they regarded as the lax moral values promulgated by New York City and Hollywood became even angrier with comics in general.

Meanwhile, the Senate had formed a subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee to investigate the juvenile delinquency issue outside the scope of organized crime. A subcommittee was formed to investigate various potential factors. Crime and Horror comics were what the Public asked the Senate to review. Senator Robert Hendrickson (R, NJ) was appointed as Chairman. The three other committee members were Sen Estes Kefauver (D, TN), Sen Thomas Hennings (D, Mo), and Sen William Langer (R, ND).

Written expert testimony gathered for the 1953 Juvenile Delinquency Hearings, of which Senator Hendrickson’s subcommittee was a part, had been conflicting at best. From presentations submitted to the Subcommittee, some experts agreed that there might be linkages to comics and delinquency, but likely only if the child already had those tendencies. Some doubted Wertham’s views that all comics were a concern, but agreed that some connections might exist. A few attacked Wertham’s methods and conclusions as well as some investigators who were in agreement with some of his findings, but most offered no research of their own to counter his clinical review work. The field stood at an impasse with little hard data and many options based on “personal expertise in the field” rather than actual studies of behavior.

The Subcommittee accepted that, in the main, the Experts’ answers boiled down to “we don’t know yet.” The Experts included Dr Wertham.

The Subcommittee had invited a number of witnesses to testify at the hearing, to include publishers, distributors, wholesalers, political and municipal officials, as well as medical experts, of which Dr Wertham was one. Other testimony and evidence was submitted prior to the hearings and included in the transcripts.

One witness demanded to be invited to testify. That witness was Bill Gaines of EC Comics.

At EC Comics, Bill Gaines had decided that he was not about to be the next image of Frank Costello, nervously shredding and wadding up paper on television in front of a Senate panel. He crafted an editorial that would help to define how the public would remember him. Gaines could have been the poster boy for “don’t send an e-mail when you’re angry, and don’t ‘Copy All’ whatever you do”.

The editorial was titled, “Are You a Red Dupe?”

Of course, Bill Gaines sent a copy of his editorial to Senator Hendrickson’s office a couple weeks prior to the start of the Hearings. Why wouldn’t he?

Dale Carnegie wept.

Senator Hendrickson, not appreciating the ever-so-subtle satire and gentle-but-wise chastisement from Mr Gaines — which was also to be shared with Gaines’ EC readers — took to the Senate floor on April 9th, 1954. His speech, taken from the Congressional Record, is shown below.

Note that Sen Hendrickson re-iterated President Eisenhower’s wish to avoid legislation as a solution within the larger problem of juvenile delinquency. This gives further credence to the truthfulness of his opening remarks on April 21st regarding the Subcommittee having no goal to legally limit speech. As stated in the previous article, both Prohibition and the 1948 Winters decision had soured some in Washington on making laws regulating behavior that were both difficult and expensive to enforce, as well as likely to be overturned through the courts. President Eisenhower had made his desire clear to Sen Hendrickson when the latter was appointed as Chairman of the Juvenile Delinquency Subcommittee.

Bill Gaines prepared his testimony on April 20th with the help of EC Comic’s business manager, Lyle Stuart. It would be an impactful, robust defense of freedom of speech and expression, of how comics were not harmful to children, and how America, Motherhood, and Apple Pie was on the side of Gaines, EC Comics, and comics publishers in general.

Next time: the Senate Subcommittee Hearings, and the Comics Code rises from its grave!

REFERENCE MATERIALS USED FOR PART B

References used here include, but are not limited to the following books and testimonial references. I strongly recommend to you all four books for your reading pleasure, and specific links that host source material from the events. These are essential if you want to understand these events.

Layers of myth have built up and surround the comic book “censorship” that followed U.S. Senate sub-committee hearings in 1954. Without reading source materials or materials that capture the most direct evidence and testimony from the principle participants and witnesses of these events, you will likely find yourself in the loop of blaming a single party due to misinformation that has circulated for decades around these events.

Book ISBNs are provided for commercial copies of these books which are available through various book sellers and outlets.

I. Books.

Seduction of the Innocent, Frederic Wertham, 1954 [ISBN-10: 159683000X; ISBN-13: 9781596830004] – The book that everyone points at, but likely few have actually read, other than for a pull-quote. Read it if you have any hope of understanding what Wertham was about, what he wanted, and how he came to the conclusions he came to over more than seven years of researching comic books, specifically crime and horror books. You likely won’t agree with all of his opinions or his conclusions, but you may be surprised by what he intended, and what he wanted to accomplish.

Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, Amy Kiste Nyberg, 1998 [ISBN-10: 087805975X; ISBN-13: 978-0878059751] – Nyberg provides a well-researched yet accessible analysis of the events associated with the Public’s concern over comic books, the juvenile delinquency problem, the Senate hearings, as well as associated events that contributed to the unfolding of events; read this book if you read nothing other than Wertham’s book.

Forbidden Adventures: The History of the American Comics Group, Michael Vance, 1996 [ISBN-10: 0313296782; ISBN-13: 9780313296789] – Vance provides a history of the American Comics Group (ACG) and its long-time editor, Richard Hughes, as well as testimonies from assistant editor, AGC freelance writer, and future academic, Norman Fruman (do some research on him as well). Chapters 11 and 12 are especially relevant to this discussion.

The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, David Hajdu, 2009 [ISBN-10: 0312428235; ISBN-13: 978-0312428235] – Hajdu provides a wealth of testimonial material from publishers, writers, and artists, as well as those people associated with comic book distributors, the CCMA, and the CCA.

II. Articles and Transcripts.

Juvenile delinquency (comic books): Hearings before the Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Eighty-third Congress, second session, pursuant to S. 190. Investigation of juvenile delinquency in the United States. April 21, 22, and June 4, 1954 – These are written transcripts from the Senate Subcommittee hearings held in New York City. Portions of the hearings were televised, to include testimony by Wertham and other witnesses. [LINK]

Website of WNYC Public Radio. The archives of WYNC host around 9 hours of the Senate Subcommittee hearings originally broadcast on radio as audio recordings. Four files of 2+ hours each allow you to listen to much of the testimony. Each linked page also offers some commentary on the audio file and its contents. [LINK 1] [LINK 2] [LINK 3] [LINK 4]

The Library of Congress Blog Site. At the link below is an excellent summary article on the Comic Book concerns, the Senate Judiciary Sub-committee hearings in New York City, and the resulting events with several good links to references. [LINK]

The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. This is an organization that defends creators from obscenity charges and other legal challenges in publishing and distributing their works. They have several articles on the publishers’ defense of comics, the ACMP Code, the CCMA Code, and their ramifications, as well as some history of the events. Amy Nyberg also has an excellent summary post with analysis from her book Seal of Approval.

The LOST Seduction of the Innocent. An excellent website collecting some rare artifacts of the Seduction of the Innocent (SOTI) book, excerpts from Dr. Wertham’s papers, as well as some samples from the example comics used in both the SOTI book and during the Senate hearings.

The Comics Forum. A number of scholarly research materials are collected here. Especially of interest may be Steven Mitchell’s thesis on the comic book controversy and two articles on Lev Gleason by Peter Y. W. Lee here and here.