Post 01 Post 02 Post 03 Post 04 Post 05 Post 06

NOTE: While I didn’t mention it at the beginning of my first post, I want to make something clear about my posts on comic books: I do not strive to be either academically rigorous nor authoritative in my analysis. Other authors have spent a great deal of time interviewing the principle actors and performing rigorous historical research. I lean heavily on those individuals who did the heavy lifting on this topic. My posts are meant to review some results of these researchers’ data and findings, as well as examining other artifacts of comic book history, to attempt to find general or overarching patterns that may inform and guide current and future creators of comics. References to the sources I use will be provided at the bottom of this and future blog posts.

How do we get comics get into our hands?

These are a few brief opening thoughts on comic book distribution. I will return to the topic in a later post. Much like Pulp Magazines, comic books started out their existence as print matter distributed by the same or similar organizations that distributed other magazines and periodicals. From 1937 to 1978, the Newsstand Model was the only way other than mail-order subscription that comics could be obtained, which was no different than the Pulp Magazine distribution model of the previous era. Comics were generally not well regarded by distributors due to their low profit margin (comics were priced at 10 cents per issue from 1937 to about 1960) and high return rate.

“Return rate”? What ever do you mean by “return rate”?

Return rate was the fraction of the total print run that was returned to the distributor by the retailers. Newsstand distribution in the years before the 1990s was based on a model of ‘pay for what you eat’. As an example, consider a retailer who orders 20 copies of Whiz Comics #25 from the distributor and places them on display until the pull date when they are supposed to go off sale and be removed from the rack. Over the course of 30 on-sale days, the retailer sells 17 copies of the comic book, then pulls the remaining three from the stand, likely to replace it with some number of Whiz Comics #26. The three remainder copies would be sent back to the distributor for a full or partial credit that could be applied to a future order. The return rate in this case would be 15%. See this Comichron page for an example of a Postal Service ‘Statement of Ownership’ and the yearly return rates versus actual sales.

Over time, rather than shipping back the entire book, the retailers were allowed to deface the cover and return proof of this action to the distributor. This usually entailed tearing off the top third or so of the front cover with the title and masthead, then returning these portions. While the retailers were supposed to dispose of the periodical after the book was defaced, it was not uncommon that these defaced copies would be quietly sold for half price or given away to customers. High return rates meant lower profits for both distributor and publishers.

Both newsstand distributors and comic book publishers were anxious to find another method of distributing comics during the Superhero heydays of the 1960s and early 1970s.

A brief aside: who were these retailers? Local comic shops? In the period between 1937 and the 1960s, exclusive comic book dealers were rarely found, and if found, they would likely not be outside a major metropolitan area. Newsstands were more common, but even they were not common outside heavily urbanized areas. The retailers of concern were located in urban, suburban, and rural areas: drug stores/soda shops, grocery stores, Five & Dime stores (such as Ben Franklin), gift shops, book stores, restaurants, convenience stores, and toy stores. Most any shop willing to devote about four square feet to a spinner rack and sign up with a newsstand/periodical distributor could have comic books.

These spinners or magazine racks were almost as common as paperback spinners, and served the same purpose: to catch the attention of customers browsing the store, or to occupy the attention of those accompanying the shopper. Often these tag-alongs to the shopper would be children. Many introductions to the comic book as an entertainment art form were made waiting for mom to finish the grocery shopping or while picking up that prescription at the drug store.

Direct-sale market proposals for comic books were considered, and a method acceptable to retailers was chosen in 1977/78, leading to a dual distribution transition period. Comics books were marketed to retailers by both newsstands and direct-market distributors for a period until about 1987 when the transition was essentially completed. After this point, direct-market distribution was almost exclusively to local comic stores that had grown up while the transition occurred.

Over the next decades, subscription services for comics would also vanish, leaving the local comic store as essentially the only game in town for comic book sales. Two significant changes resulted from direct-sales distribution: no returns (“eat all you take”), and potential minimum order numbers of selected issues (“take all we want you to eat”). While good for distributors and publishers, these conditions would become a point of contention over time for both comic stores and their customers. These changes also made tracking the actual sales numbers of titles much more difficult, as distributors often didn’t release those data to the public.

The question I will leave at the end of this brief introduction to distribution of comic books is: who services the comic book readers in rural and small suburban areas that aren’t large enough to support a comic book store? Do hard copy readers even exist in these locales in the 21st Century?

Local comic shops (in my admittedly limited experience with only several dozen) don’t often appear in areas with populations under about 30,000 people. Few retailers of the newsstand method mentioned above chose to keep comics in their establishments with the overhead of using a second distributor for low-volume, no-return, low-margin profit items such as comic books. Comic books vanished from the pre-1978 retailer locations over an 8- to 10-year period. Much like the Thor Power decision, this impacted used book stores that traded in comics, as well as beginning to remove the comic book hordes from rummage and yard sales, swap meets, and other locations where used comics might be found. The old comic book owner was suddenly in the middle of a collectors market.

Enough of that discussion for now. It will serve as an opener for a more detailed distribution discussion later.

What contributed to making 1960s Marvel Comics a success, and what killed it: the 1968 Sale.

NOTE: I lean heavily on two sources for much of this section. The first is Chris Tolworthy’s site, “The Great American Novel”, which is a work-in-progress love letter to “The World’s Greatest Comic Magazine”. While I don’t agree with some of Chris’ analyses on what Kirby’s artwork intends, disagree with his interpretations of the FF saga character-by-character, and believe that the “Stan vs Jack” debate is a false dichotomy, his site provides a wealth of information on the Silver and Bronze Ages of Marvel Comics, as well as some pertinent DC Comics data. The other site of interest is Comichron. It gathers comic book distribution and sales data from the 1960s USPS Statements of Ownership, as well as Direct Market data from distributors (yes, plural–there was once many more of them than just Diamond) to provide rough snapshots of comic sales and popularity year-on-year.

The transition for comic book companies out of the Golden Age of Comics was not an easy one for most of the companies that survived the downturn in superhero comics popularity after World War II, the congressional hearings on suitability of comics for children (Fredric Wertham), and their own poor planning for the audiences of the 1950s. Timely/Atlas was the precursor of Marvel Comics and was owned by Martin Goodman. Their superhero titles were pretty much shuttered by 1949 due to falling sales. These cancelled titles include Namor the Sub-Mariner, the Human Torch, and Captain America. Stan Lee was the company’s Editor (essentially the Editor-in-Chief), taking over from Joe Simon in 1941 until 1972 when he left that position to take the role of Executive Vice President and Publisher, roles he would hold until 1996.

But, Stan was more than an editor at Timely/Atlas. He was one of the primary writers for their stable of comics, which included horror, western, romance, mystery, and crime/detective books. Due to the loss of his distributor in 1957, Goodman was forced to cut and drop most of his current titles (see this article for how many books stop at 1957) and sign a contract with National Periodical Publications to distribute Atlas/Marvel comics. If you recall, National was the publisher of Superman, Batman, and other comics that are today known as the DC Comics stable.

Yes, that’s right. DC Comics (National Periodical Publications) distributed the 1960s Marvel Comics titles that eventually overshadowed their own titles. What a world! What a world! What a world!

The agreement did come with restrictions that Goodman could only publish a limited number of titles, which is thought to be one of the reasons that Tales of Suspense hosted both Iron Man and Captain America, Tales to Astonish variously paired Ant-Man/Giant-Man & the Wasp, Sub-Mariner, and the Hulk, and Strange Tales had split features of the Human Torch, Doctor Strange, and Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. It would also explain why the original book for the Hulk was cancelled after its sixth issue. If it wasn’t selling up to par–they needed that space for another title that did!

Stan started under the new distribution contract with the at least these titles in his stable:

- Patsy Walker

- Patsy and Hedy

- Millie the Model Comics

- My Own Romance

- Love Romances/Teen-Age Romance

- Journey into Mystery

- Strange Tales

- The Outlaw Kid

- Two-Gun Kid

- Rawhide Kid

- Kid Colt, Outlaw

There may have been more titles that made it into the Marvel Superhero Era beginning in 1961 (I’m still researching that detail), but these 10 were there for certain. However, the biggest bonus Stan had at the time was the group of artists that gravitated to Marvel to work on these books. Jack Kirby, Joe Sinnott, Gene Colon, Steve Ditko, George Roussos, Dick Ayers, John Buscema, Paul Reinman, and others who would form the core of the 1960s Marvel Bullpen of artists were among the creators working on these books, then stuck around for the fun later.

Stan and company saw the success of National Periodical’s reboot of The Flash and Green Lantern, and then the rolling these two heroes plus Aquaman, Wonder Woman, and Martian Manhunter into the Justice League of America in early 1960, courtesy of Gardner Fox. Lee and Kirby’s first foray into superheroes would be the Fantastic Four in November 1961, followed by introductions of Ant-Man, the Hulk, Spider-Man, and Thor in 1962.

I’m not going to recap the Marvel Superhero play-by-play. Been done elsewhere, and likely done better than I could. What I do want to point out are Stan’s writing and editorial responsibilities under Marvel from 1961 through mid-1972 when he left the Editor-in-Chief job to become Marvel’s Publisher. He was not coasting, as some might think.

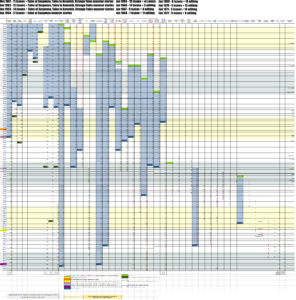

This image shows Stan’s responsibilities from this period. Click the image to scroll around–it’s a large image. The light blue areas are those titles that Stan was credited with writing. Stan may have had other people editing in the mid- to late-60s, but that is uncredited if he did. Therefore, Stan is assumed, by me at least, to be the sole editor from 1961 through 1972 when he left that position.

Current counts on the above image for all years in January (except November 1961 / Fantastic Four #1) indicate that Stan was responsible for and credited with writing and editing the following number of titles PER MONTH at Marvel Comics (data from the Grand Comics Database):

Nov 1961 – 11 titles*

Jan 1962 – 12 titles*

Jan 1963 – 14 titles*

Jan 1964 – 17 titles*

Jan 1965 – 19 titles*

Jan 1966 – 14 titles + 3 editing

Jan 1967 – 9 titles + 9 editing

Jan 1968 – 7 titles + 11 editing

Jan 1969 – 6 titles + 14 editing

Jan 1970 – 5 titles + 15 editing

Jan 1971 – 4 titles + 14 editing

Jan 1972 – 2 titles + 9 editing

* Monster/SF stories in Tales of Suspense, Tales to Astonish, Strange Tales may also be done by Stan.

Yes, Stan had other writers for some of this period, but GCD data is designed to accurately reflect credits as listed in each of these books. GCD also reflects those other writers’ work as Stan steps away as writer through the 1960s. Some of the titles were staggered bi-monthly, so that provided some breathing space, but Stan held responsibility for the book month-to-month. Can credits be fudged? Sure. But, we will run with the info as given in the books and collected by GCD. Imagine that workload every month for twelve years. If this is accurate, then I am surprised Stan and the Marvel Bullpen survived it, even though there were 27 titles at Atlas/Timely before the 1957 distributor loss.

As I stated above, I believe the “Stan vs Jack” debate is based on a false dichotomy. Did Kirby and Ditko create plots and characters apart from Stan Lee input? Probably so. Was Stan only providing dialog for many titles, not full plot and scripts? Not a doubt in my mind. Did credit for some activities get mis-attributed over time and due to faulty recollections (and owner and executive-level shenanigans)? Can’t believe that it didn’t.

But, nothing may have come of the Marvel Universe if this team had not come together. The creative engines of Kirby, Ditko, Heck, and other artists in the Marvel Bullpen generated the art, some of the plots, co-created characters, and crafted events, while Lee crafted the dialog and overall story continuity that held the whole together with common threads and events. Pull away one or two of this cadre, and Marvel might have gone the route of a failed experiment.

What this insane writing and editing method created was internal consistency and continuity over the whole of the superhero line through the 1961 to 1968 period.

As Chris mentions in his discussion on Continuity, the concept of continuity need not fetter creative writers or artists, any more than pointing out that Ben Grimm doesn’t wear a cape. There are rules and history to comic book characters in the 1960s Marvel Universe that give it something that Edmond Hamilton and Gardner Fox were slowly working toward with the Superman Family, Krypton History, the Legion of Superheroes, the Justice League of America, and the reboots of Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, and Atom–namely filling out a history for characters that had only been portrayed as having unconnected adventures and disconnected timelines from those events.

Specifically, 1960s Marvel provided verisimilitude and continuity to characters, allowing characters to experience consequences that mattered to the story, and thus to the readers. When Sue and Johnny’s father died in Fantastic Four Issue 32, it was a permanent change for them and the rest of the team. When the Thing crushed Doctor Doom’s hands in Issue 40, it was a driver for Doom’s revenge twenty issues later in Issue 60 — there was memory of the insult and damage, the thirst for Doom’s revenge upon the Thing, creating an element of verisimilitude for the readers. This is how readers expected the arrogant Victor von Doom would behave–it made sense and it felt “real” to them.

Chris’ page on “How to Make Great Comics” highlights this formula, but I believe that Chris, Stan Lee, and Jack Kirby were on the wrong track by calling it “Realism”. I believe the word they wanted was “Verisimilitude”–it needs to feel or appear real enough to generate belief. It does not necessarily need to be “real”, but rather “real enough”. The scientific jargon Reed Richards uses doesn’t have to come from a real-world physics text, but it needs to be believable enough to the reader to give that impression to the story. The verisimilitude benefits from continuity and is reinforced by it. Discontinuity tends to pull the reader out of the story.

What is clear is that when Marvel was sold in 1968, the bonds of continuity and verisimilitude were being damaged and ultimately removed. With that removal, the quality of the books began to suffer. Under the sale, Marvel was no longer under the agreement with National Periodicals to limit the number of its titles, and that number almost doubled in two years. But, the creative engines that built the 1967 Marvel were leaving or had left. Working within those externally imposed limits may have also contributed to the 1960s Marvel’s sharp writing, tight pacing, and innovative art. The quality of the books declined rapidly with the onset of the 1970s, and this was quickly seen in the sales.

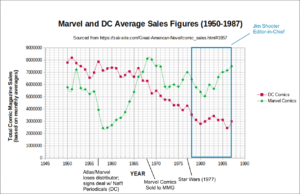

I re-created the graph that is on Chris’s page discussing the Marvel Universe and how it lost its way. My version removes some of the sharp peaks and adds a few real-world events against the sales curve. Note that the Marvel upward peak in 1977 is likely from Roy Thomas convincing Marvel senior leadership to allow him to create a 6-issue mini-series of the new movie Star Wars, which is credited with saving the company from bankruptcy.

That 1968 sale and the change in the fortunes of Marvel are well-aligned, though not causally linked via this data. So we have correlation vs causation event here — but correlation is strongly predictive. Stan brought over 35 years of experience managing creative teams and writing dialog for comics to the fore for Marvel’s success. Notice how many people attempted to assume the Editor-in-Chief role after Stan left it, and were only in the job a year or two. It was not until Jim Shooter took the Editor-in-Chief position that Marvel’s sales fortunes began to turn around. Shooter demanded hewing to a universal continuity for Marvel. Though the creative talent chafed against it, sales improved throughout Shooter’s tenure, and declined after his departure.

It is worth observing that the two Editors-in-Chief who practiced or demanded continuity were the most successful in financial benefit to the company.

Chris has several pages on his site under the headings “Marvel Comics” and “What Went Wrong”. These are all worth your time to read if you are interested in how Marvel Comics lost its way, partially recovered under Jim Shooter, then resumed its downward decline with DC Comics.

What conclusions can we draw from this information?

History should be a good teacher when it comes to running a business in a specific sector. Look for mistakes that others make, and learn from them, rather than making the mistake yourself. Based on the following examples, I’d guess that business leaders just don’t learn without a solid PowerPoint summary slide.

In the early 1940s, Lev Gleason Publications was waxing poetic on the competition with only four published comic books in their stable — Silver Streak Comics, Daredevil Comics, Crime Does Not Pay, and Boy Comics (starring Crimebuster), and featuring art by the stellar Charles Biro. In 1948-1949, the publisher was smelling money and chose to more than double their line in that period. The company talent couldn’t keep up with the pace and quality suffered. Gleason went out of business in 1956.

Over a three month period in 1975, DC Comics launched the “DC Explosion”, releasing 57 new titles into their stable. This was during the 1973-1976 comic book downturn. Economics forced DC to reverse their decision in 1978, resulting the “DC Implosion”, where the leadership chose to cancel 40% of their entire line. Cancellations were made before many story lines in the titles were concluded, further angering readers who had stuck with the company through this period.

A third example was Martin Goodman’s Seaboard Publications’ Atlas Comics. Formed by Goodman after his sale of Marvel Comics in 1968, Atlas Comics began releasing a flood of titles in mid-1974, including 5 magazine titles and 23 comic book titles. Even though some well-known and regarded creators worked on these books, creative teams were swapped out at the issue 2 or 3 mark, characters were redesigned and renamed mid-storyline, and no connectivity between titles existed. No book made it past issue 4, and the company shuttered in late-1975.

Post-1968 Marvel is a similar case of assuming your resources are expandable without sacrificing quality. Typical ‘suit’ move. And this would not be the last time this would be tried. Both Marvel and DC have difficulty with ‘lessons learned’.

A number of points for consideration are raised by Chris in his analyses of what made Marvel great and the cost of comics, and they deserve your attention and time to read.

These points stand out for me:

(1) Don’t make Stan’s cardinal mistake of Post-1968 Marvel (“Fans don’t want change; they want the illusion of change.”) No. Your audience wants meaningful change, change that matters, and change that impacts the story. They want verisimilitude with their story, and continuity aids that verisimilitude. Don’t be afraid to set out some basic rails that bound your story, your characters, and your book. Continuity is appreciated by the audience. Continuity is not your enemy.

(2) Quality is vitally important with verisimilitude and continuity. Quantity may have a quality all it’s own, but in comics all that means is that you may be creating fireplace kindling rather than audience entertainment. That doesn’t mean that all your art must be at the level of Alex Toth, or that your script features award-winning prose every time. You cannot gloss over the need for your best effort in your work. Producing more books or titles probably will not cover over your unwillingness to deliver quality. In fact, there is strong evidence that ignoring quality for quantity may destroy you in short order.

(3) Listen for, ask for, and act on quality feedback. Your customers may not always be right, but you’d better understand what they are saying and why. Your artistic muse needs to be balanced with what the audience wants for its entertainment. None of this means compromising your morals or ethics. As modern comic stories have demonstrated, retrofitting popular characters, or killing off then resurrecting characters repeatedly, then putting those scenarios on reset-and-replay, probably will create some heartburn with a significant portion of your audience. And, you may never know it because the majority will likely just walk away and not come back to tell you.

That’s it for now. More on distribution next time.

Background Links.

Kleefeld on Comics – Sales Figures

Charles Biro

Progress and Process, Part 1

Progress and Process, Part 2

Comic Book Prices versus Minimum Wage

Grand Comics Database

The Cover Browser

The Comichron

Chris Tolworthy’s ‘The Great American Novel’

I think the unstated point which lurks here is that Marvel should have retired most of its old superheroes in the period 1986-95. Let Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson retire as a married couple some time in the late ’80s to early ’90s. Do the same with Johnny Storm and Alicia Masters. Don’t retcon the old marriages out of existence. Just retire the old characters in a dignified way. Marvel at its best implicitly observed the One-Third Rule which should mean that 3 decades of comic-publishing time equals at least 1 decade in the lifetime of a character. Hence by 1991 Reed Richards should be in his late 40s since he seemed to be in his late 30s in 1961. Let the old X-Men really retire out of the picture with just occasional appearances as an aging Scott Summers and Jean Grey show up now and then.

If Marvel had enacted this as a company-wide policy in 1986-95 then they could have experienced a great rejuvenation. But by trying to endlessly prolong the older characters they really wore things out. Part of the problem is that there is no clearly defined expiration date with such artistic products and so the problem can seem to sneak up on everyone. A food product may be known to spoil after 2 weeks, so you know to consume it before then. A mechanical product like a lawnmower may have a breaking point at which you know it needs to be replaced. But how does one decide when the run for Peter Parker has gone on long enough and the character should be retired? 3 decades strikes me as a safe bet, but it’s impossible to give a technical proof of that.

Although there were haphazard moments at Marvel in the 1970s, some of the most creative work was done during this period. A lot of the best was done in comics that were not the primary sellers but which opened opportunities for inventiveness. Jim Starlin wove the original Thanos stories Captain Marvel and Adam Warlock while intertwining the Avengers with it. Doeg Moench with Shang-Chi, Marv Wolfman with Dracula, were examples of secondary characters seeing a long intriguing run. Even though today people regard the X-Men as well known, at the time when Chris Claremont took it up it was regarded as a failed series which was open to innovation.

But by the late 1980s Marvel really needed to retire a host of characters in order to set things in order. When Jim Shooter was fired the turn was clearly against this. One gets the impression through Shooter’s run as editor that there was some preparation for a big retirement of older characters. Then after 1987 the atmosphere changed and one can no longer read such a sense of rejuvenation in the Marvel Universe.

‘Marvel Time’ was the death of creativity at Marvel Comics. Of that there is no doubt. DC had frozen Superman at 27 years old in the 70s, but this was just a confirmation and continuation of what they had inherently done with the character since its debut in 1938. Marvel had the opportunity to stay out of that cycle from 1961 to 1968, but the company chose the same failing path for superheroes as DC after the 1968 sale to a corporate raider.

I’d argue that the better bet would have been to start changes to the superhero titles in 1968. Franklin Richards appeared in FF Annual 6. Reed and Sue were looking for a Connecticut home away from the city in Issues 87-90. Family linked elements appeared in following issues until Kirby departed after Issue 102. Chris Tolworthy goes into more detail, but his thinking parallels mine from decades back.

Reed and Sue might go into a semi-retirement where they spend more time at FF HQ and at home with the children, direct FF activities remotely, and new team members replace them for day-to-day adventures. Either Ben or Johnny lead the new FF team, composed of Crystal and one other new member. Eventually, Franklin joins the team after he becomes a teen-ager, and Johnny and Crystal depart or move to semi-retired status to raise their family, and their kids, with Ben and Alicia’s join the team as they grow older. The Fantastic Family continues apace, but grows organically for each new generation of readers.

Cyclops and Marvel Girl might marry and join Professor X in finding and training the next generation of Mutants. Angel would lead the new X-Men ADVON team made up of he, Iceman, Beast, Polaris, and Havok. Existing members slowly retire to Xavier’s mansion or other lives as the new mutant trainees replace them. Dave Cockrum started them down this path (I believe he was the impetus for the new X-Men, and the bigger driver than Claremont during his tenure), but X-Men slid into the same static rut as any other superhero book.

Avengers could have continued to be the JLA of Marvel and swap team members every so many years, and be a showcase for new superheroes.

Other books could have done similar things, and morphed into larger and more complex stories, or just been shuttered if the direction was lost or if the book’s popularity was really based on the creative team and not the appeal of the character itself (e.g. Steve Ditko on Doctor Strange, Jim Steranko on Nick Fury).

Marvel and DC both went back to trying other genres in the late 60s and the 70s. Both lack of firm editorial direction and economic instability were against them, but it wasn’t for lack of trying new things. The issue was that most of these things Marvel and DC tried were dark, grim, and often nihilistic. This paralleled SF/Fantasy from Big Publishing. Again, I’ll tag back to JD Cowan’s investigation of the pre-Star Wars vs post-Star Wars period in these must-read analyses that he wrote.

I think Star Wars was what put some interest into audiences and stimulated comics in the 1978 and forward periods, at least through the early 90s. Jim Shooter was at Marvel at the right time to take advantage of that, but it might not have come to much if Roy Thomas had not been adamant about bringing the Star Wars licensing to Marvel in 1976/77 to stave off bankruptcy.

Consider also that 1985 was likely too late to consider redirection or retirement of IP. The Direct Market was already turning to IP spin-off products as a larger revenue source for publishers, distributors, and local comic shops. The opportunity to make these changes would have been in the very early 70s during the downturn, when the potential for other genres was being attempted, and changes could be justified by poor sales and unfavorable economic conditions.

By the late- to mid-80s and early 90s, 4 Superman films, a Supergirl film, the Burton Batman films, TNMT, Rocketeer, and several Marvel TV movies had been made. More were optioned for production, so making a Hollywood deal with your character was now on the plate, further cementing the freezing of the characters in time.

The likelihood for change after 1985, or even 1980, was slim to almost impossible to occur. Only full-out failure of the superhero trope in other media would have allowed for the type of change you are talking about here.

Although I’m sure that you’ve accurately described some of the thinking that went on, I would have to disagree that going into movies needed to mean freezing the comic characters. I think it could have worked to stop producing Spider-Man comics but go on with 3 decades of Spider-Man films. These are different genres and shouldn’t be too tightly bound to each other.

Comics by their nature require a bit of a nerdy persona for a reader to have the patience of digging through various old issues and crossover series to follow a plot line which often is spun somewhat off the cuff but in a way which gives the impression of having been planned as a great epic. Movies are the sort of thing where if a normal fellow is looking for an easy way to take a chick out somewhere before trying to make a move then a reasonably entertaining adventure film should be a natural draw. So the Star Wars movies will draw in huge bucks whereas the intricate plotlines in the comics will be passed over outside of a niche audience.

But this problem could have been addressed by retiring the Fantastic Four from the comics and then producing a wave of Fantastic Four films while starting something new in the comics. The films would likely have been successful and widely promoted by old comics fans, while the new stuff could grow in the comics. Rinse and repeat every other decade and that could have meant a steady source of film blockbusters following up from now classic comics.

As I understand it, Chris Claremont ended up on the X-Treme X-Men because he got into trouble with editors who wanted him to play up to an expected X-Men movie. I would say that Claremont was right to resist this. The attempt to try to bend comics production around movies is a bit like if someone who has operated a famous successful family diner for decades decides to revamp the whole business in an effort to duplicate the success of McDonald’s corporation. The likely effect is to spoil the original business model without matching the real successes of what is imitated.

We may be talking past one another a bit, so I apologize if I missed your original point on this.

I agree that there was no need from an artistic perspective to tie the comic books to the films, and I didn’t mean to imply that it was necessary if that was how you read my comments. The films could feature any version of a character the producer, director, and writers chose, from any era that featured the character in question, or even feature retired or ‘dead’ characters. No matter what the status of the comic characters development, the movie development could proceed independently.

The editorial policies from 1968 forward do not indicate that anything but ‘Marvel Time’ was used for the next several decades. That ‘freeze’, or ‘slow down’, on character development *did* occur within the comics, as stated by Marvel staffers of that period. One may argue if Stan or subsequent editors created these policies or if it was from executive leadership and owners, but the freeze occurred.

From the practical standpoint, none of the writers, artists, or editors had final editorial control over what the owners of the comic companies chose to do with the characters. The incident you speak of with Claremont may be when Professor X’s legs were restored and he could walk. Higher ups in the company directed that Xavier be placed back in the wheelchair due to other contractual considerations. There was certainly nothing wrong with Claremont walking away from this situation, but the decision about the book’s direction was not in his control. The IP was in the control of the owners, not the creatives who were essentially ‘work-for-hire’ on these properties.

My argument was that if you wished to make changes similar to what you were recommending, the time would have been prior to 1968 or just after, when both the US economic downturn and the search for other genres at Marvel and DC might have allowed significant changes to these books. The post-1985 world was far too late, due to the mindset of the people who were in control of the IP, as well as deals being made for other media using the IP.

What you describe in terms of comic production is what the last 20 or more years of Marvel has been — warping the comic book business to match the movies, after the movies copied the comics, after the comics tried to make themselves sale-worthy to be optioned to film. The business model of the magazines has been bent out of shape and is close to broken, if not already so.

I agree that there was a slowdown in the frontline-selling comics, although I wouldn’t call it a “freeze” and things were often different in the secondary lines. Just to take one character: Tony Stark. At the time of the 1968 publications he was still involved in arms production. During the early 1970s, as part of the detente era, Mike Friedrich had him convert to peacetime industry out of the arms race. That was certainly portrayed as a major development in Tony Stark’s life. Not really a freeze on character development. During the period up to 1968 the main character development was simply Tony Stark’s decision to back off from Pepper Potts and let Happy Hogan run with the ball. So I think that more character development got going with Tony Stark after 1968.

The peak of that character development, in my opinion, was in the 1980s when Obadiah Stane wrests corporate control of Stark International away from Tony Stark, while manipulating him into a resurgence of alcoholism. In recovering Tony Stark finds himself sharing his secret identity with fellow Avengers. The final confrontation with Obadiah Stane should, in my opinion, have been followed by a decision to slowly wrap the series up within a few years. The best thing I could imagine would have been if Tony Stark and Janet Van Dyne had retired together.

For a while Steve Englehart had brought back Maria to Hank Pym and that would have been the perfect way of resolving everything across the board. Hank retires with Maria, Tony with Jan, and any further appearances show them as an aging support-cast. Instead Marvel decided to just keep on going with Tony Stark as Ironman and this eventually led to the silly idea of replacing him with a teenager from an alternate dimension. But I think if it had all been wrapped up in the late 1980s then it could have come out looking like a good solid run across a quarter-century.